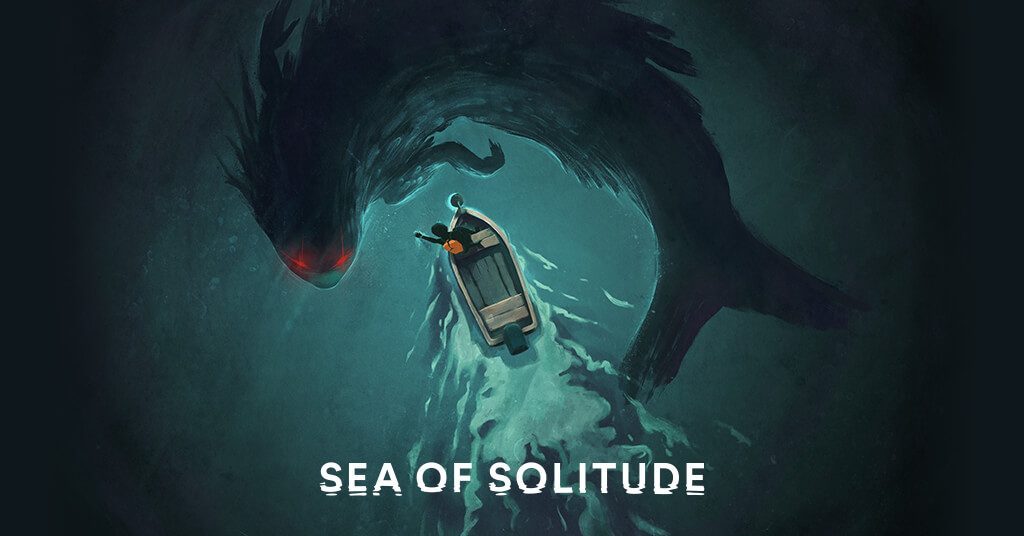

Unfortunately, as relatable as Kay’s circumstances are, very little room is allowed for reflection. They’re all relatable traumas for a fantastical psychic space. The ligature that makes it work is the mundanity of Kay’s traumas-unhappily married parents, a neglected sibling, a boyfriend she hurt by trying desperately to help. A half-submerged sea-monster, a beautiful crumbling snow wolf that reveals the tragedy beneath, an exploded office tower filled with flaming vents and a chameleon lording over it: This is the symbolic dissonance Sea of Solitude deals in. Psychology is messy, murky, and Sea of Solitude gets at that with inconsistent metaphors, opaque symbolism, bottled messages to the self (an intertextual nod to The Police), and gameplay that shifts with the protean landscape we’re required to traverse again and again. My mother once said this makes them cook faster. I’ve broken the noodles in half before putting them into the pot. The living room of my lost childhood home transported to their lost beach house, while I make a meager spaghetti for our dinner. How the build up to their divorce was them waging war, lobbing my baby sister back and forth like a live grenade. Or how my stepfather switches Noh masks and no one can predict what meaning the next one will convey, or what’s underneath (if anything at all). I explain my mother as a giant squid, shooting ink out to escape, unaware of how her long, long arms can constrict around her children. Different representations for different traumas, all separate but intersecting. As with Kay’s traumas, we often have to use symbol and metaphor to get at our own, to understand, communicate, and reckon with things we’d often prefer not to name, let alone realize, that are too immense and painful to grapple with initially. We spend most of the game touring psychic landscapes as we platform across sorbet-colored European architecture or skim over the sea of the unconscious in our little propeller boat. As grounded as it is, Kay’s journey is far more interested in a grounded metaphorization than clinical realities. This is a game about mental illness, even if it eludes that distinction. In this way, it mimics my own experience with trauma and recovery.

Answers are given and taken away, and then recapitulate and recontextualize themselves. Kay-ashen, red-eyed, and monstrous-is our protagonist. The kind that builds up while we push it down and ignore the blood seeping from our knees and elbows as we try to carry on-distracting ourselves from how it crusts on us like barnacles, loading us down until we no longer recognize ourselves or our loved ones. The sticky, mud-like kind that cakes and cracks and stings because of the thousands of cuts and abrasions we’ve accumulated. So, only a few minutes into Sea of Solitude, when a monstrous, feathered or furred aquatic monster-woman stopped me dead in my tracks and screamed that I am a selfish piece of shit? I felt pretty called out.

When the sucking sensation, like a black hole has opened through your torso, makes your ears ring with just how unbearable you feel as a person. And as protective as these measures are, when the sense of isolation becomes overwhelming, it’s hard to ignore that this drowning feeling is partly one of my own making.Īnd that’s when the shame drops. It takes a lot to open myself up to relationships filled with as much hurt as joy, as draining as they are innervating. I go through this because it’s too unbearable, too exhausting to be vulnerable. Sometimes when family calls, I just let the phone ring, not even hitting the ignore call button. My sister and I have engaged in a mutual, unacknowledged communication armistice for nearly a decade. He’ll ask about what I’m writing, and then go off on an MSNBC-fueled tangent about Donald Trump, or tell me about how he’s modding flight simulators now. Half the time I’ll pull out my phone, hesitate over the call button, and then flip over to Twitter instead, desperate for any awful thread I can bury myself inside of. It’s been years since I’ve seen my mother.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)